Ferrel D. Moore

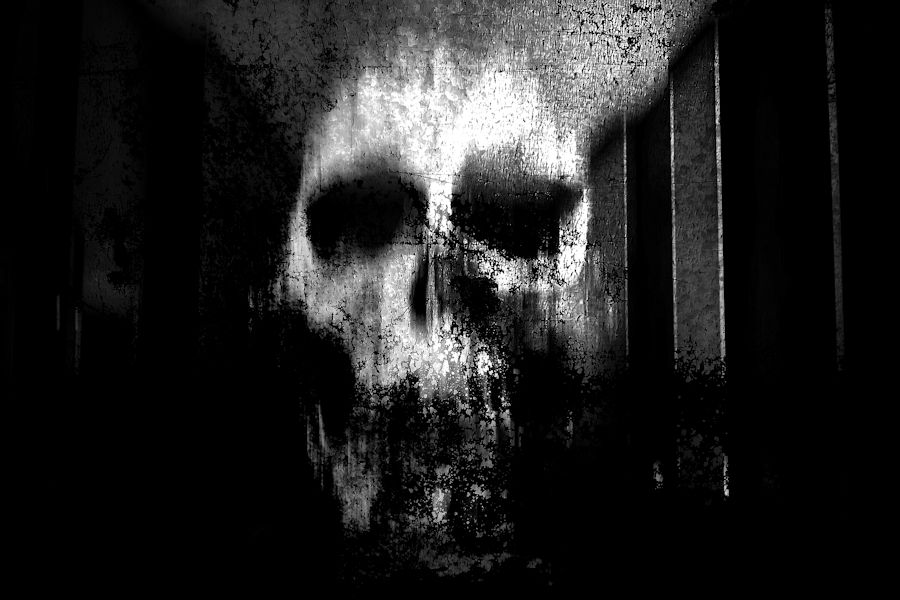

“There,” Mary said, extending a bony finger toward a windowless mahogany door halfway down the hallway.

“Okay,” said Edgar, drawing out the word while she thought of how to continue. “I see the door, but what’s the question?”

“Ah, Jesus, haven’t you been listening to me?”

“Well, of course,” he sputtered, “but you talk so much sometimes I miss a little. Or maybe I forget parts. At my age I’m lucky to remember my name.”

Mary closed her eyes and felt the sadness take over. If Edgar didn’t care what she was saying, then who would? She had never married, all of her friends were dead except for Edgar, and sometimes, Edgar didn’t remember who she was.

“Listen to me, Edgar,” said Mary, softly tugging on the edge of his gown to get his attention, “that’s the door. That one down the hall. Anyone that goes in there dies. Don’t ever let them take you into that room for any reason. Do you understand me?”

“What did you say?” asked Edgar.

Mary sighed. Once upon a time, she had been beautiful and rich and in control of her life. Now she was poor and living in a nursing home with no family to take her home. She had lost her health, her money, and her youth as efficiently as if she had planned for it since birth. Mary did not want to lose her last friend as well.

“Haven’t you noticed?” she asked, but she knew that he hadn’t.

An attendant named Ricci was the one who wheeled them in through the mahogany door when it was their time. Mary had written down the name of each elderly patient he took through that door, and then slid the paper back underneath the television each night so that the staff would not find it.

He rolled them to their death on a wheelchair.

Mr. Chirac, the arrogant good looking one, was always waiting inside and sitting behind the black desk that looked as long as a coffin. No one ever saw Mr. Chirac enter or leave the room. But he was always there, leaning back in his leather chair, the drapes pulled, and his banker’s light on. Mary had never seen so much as a paper on that desk.

Now she was afraid that Ricci would be coming for her soon, because she had peeked around the door one day and seen Mr. Chirac staring back at her with his dark eyes. His elegant fingers were steepled in front of him as though he were considering who to have Ricci wheel into the room next. Mr. Chirac had smiled faintly and pointed his steepled fingers at her. Mary had pulled back, trembling as though with palsy and began to cry. Moments later, the door closed without a sound.

If Ricci took her through that door, then there would be no one at all left to protect Edgar from the devil named Havier.

“But why?” asked Edgar. “What if they do? We have to go where they take us.”

“I don’t know what I’d wish for if I had the choice,” Mary said. “For you to have a functioning brain or a functioning penis or one day a week for both. Where’s you mind, Edgar? Where’s your testosterone? We don’t always have to go where they take us.”

“But they could put us out,” whimpered Edgar. “Where would we go then? I don’t have a car; I don’t have a house anymore. Maybe I do. I don’t think so. It was on Maple Street. Have you ever seen my house? God, I loved to work in the back yard. Annie can’t do much gardening anymore.”

“Annie’s dead,” said Mary.

“Annie who?”

“Shhh,” said Mary. “He’s coming.”

“Huh? What’s that?”

Mary was staring down the hall at a muscular young man with sleek black hair walking slowly toward them. He wore an orderly’s white t-shirt and tight white jeans and sneakers and fifty years ago Mary would have fluffed her hair and stuck out her chest at his approach. Now she lowered her head. The gray-blue light of his eyes had been too much to look at, and she could not trust herself to meet his glance as he approached.

“Well, well,” said Havier as he approached them. “My two favorite twilight friends, sitting in your wheelchairs halfway between one end of the hall and the other. Are you tired, Mary? You must try to perk up, to have some fun and enjoy all these special years that you have earned.”

He smiled an LED bright smile and opened his arms as though he were about to embrace the two of them, wheelchairs and all.

Mary looked up at Havier, and then looked away from the door that she had pointed out to Edgar.

“Just out for a stroll,” she said, then looked at Havier again and winked. “Girl’s got a right to go out on a date every now and then, doesn’t she?

Havier clicked his tongue. “Mary,” he said, “you are so hot blooded. You should have been born Latin. And at your age… I am so proud of you. But do the two of you use protection? You should ask me to bring some in for you. They have them in colors now, did you know that? Hey, Edgar? What do you say to that? You are a man. Such things are not your responsibility, but you must sometimes think for two.”

Mary’s stomach roiled when she saw Havier lean toward Edgar and place one palm on each of the armrests of his wheelchair. Mary noticed Havier’s muscles flex as he squeezed the armrests, and she was certain that Edgar did as well.

“You must have something special for this woman to find you so attractive. What’s your secret?” asked Havier.

Edgar stared up at Havier and Mary felt like crying. She watched Edgar blink his eyes and take a small gulp to fortify himself the way that years ago he would have taken a shot of whiskey. She looked at Havier’s hands as they slipped down to adjust Edgar’s gown.

“My, my,” he said. “What you got down there Edgar? You hiding some special equipment?”

“Don’t touch him,” said Mary.

“What’s that?” asked Havier, his eyes widening in feigned surprise. “Mary you wound me like… like a paper cut across my heart. I’m just tidying Edgar up so he’s going to look good for you.”

“His skin,” said Mary. “I meant his skin is so sensitive because of his medicine.”

“All of his skin?” asked Havier. He winked at her.

“I don’t know what they give him, but he’s sensitive to the cold, too,” she rattled.

“Perhaps he needs warming,” said Havier. “Perhaps his blood is thin. I could come in and check on him later tonight when the lights are out.”

“No,” said Mary. “He’s a light sleeper. When he wakes up in the night he gets scared. He doesn’t like the dark.”

“I don’t like the dark,” put in Edgar. His mouth barely parted when he spoke, as though he were afraid of being heard.

Mary looked at Edgar’s forearms and saw that the surface of his dry, blotched skin was wrinkled with fine lines that looked like cracks spiderwebbed across a dry creek. Once the skin must have been pulled taught across finely sculpted muscles. Edgar had been a carpenter working construction. His shoulders must have bulged and stretched his t-shirts tight as he wielded his hammer. Now he cowered under Havier’s too personal stare. His cheeks were flushed and his hands fidgeted. How could God allow a fine man like Edgar to degenerate to such a state that he flinched before a pervert like Havier?

“In Greece,” smiled Havier as he leaned forward more towards Edgar’s good ear, “they had a good system.”

Mary’s stomach flipped when she thought that Havier was going to put his tongue into Edgar’s ear. She wanted to scream, but she had seen what happened to old people that made noise.

“You’ll like this, my dear friend,” continued Havier. “Two men would sleep together to, you know, keep warm. And at night, in the mountain passes or when sleeping at night in the forests, they could hold each other and keep each other warm. How does that sound to you Edgar? It’s just a thought. Or do you prefer an old woman with thin blood in your bed?”

Havier leaned still closer toward Edgar, and the old man squeezed his eyes shut.

Mary was about to scream, when she felt a shadow fall on them, and saw a hand the size of a catcher’s mitt wrap its fingers around the back of Havier’s neck, then yank him backward and straight up onto his toes. Havier wiggled and began to choke. His face flushed the color of a radish.

“We got a problem here, Havier?” asked a deep voice.

Mary turned and saw Ricci holding Havier two inches off of the ground. She could see the acne craters that pocked Ricci’s face and the scar that cut from the right side of his lower lip straight down to his chin. He had thick ears that stuck out from the side of his head as though someone had pulled too hard on them when he was a child. Mary thought he looked quite handsome at that moment.

Havier shook his head side to side as hard as he could with Ricci’s hand locked around his neck.

“No,” he croaked.

Ricci looked at him with brown pig eyes.

“Good,” he said. It took him nearly a full minute to lower Havier to the ground. “Mr. Chirac don’t like problems in his establishment. He has a lot going on so he has to keep things organized, you got that?” Havier’s heels touched the floor, but Ricci kept a tight grip on the man’s neck.

“Okay,” gasped Havier.

“Here’s the way it is with Mr. Chirac,” said Ricci.

“Okay,” repeated the orderly.

“You know how it is with Mr. Chirac?”

“No. Please don’t hurt me.”

“Do you know how it is with Mr. Chirac?”

“I said no. Please. I was just having a little fun. Trying to entertain poor Edgar─.”

“Shhhh,” said Ricci, and he held the index finger of his other hand to his lips and blew across the tip as though it were the barrel end of a smoking gun.

Mary saw Havier blanch and crunch back like he was preparing to be hit.

How do you like that, you bastard? she thought.

Edgar was watching with his eyes wider than she had ever seen them.

“Whatever you say,” said Havier. “Please don’t hurt me.”

“Who are you?” asked Edgar.

Ricci looked at him, and Mary felt her heart sink. The hulking bear was there for a reason.

“I’m Mr. Chirac’s personal assistant,” said Ricci. “I take care of doing what he wants done. And right now what he wants done is for me to make it clear to this piece of shit that if he doesn’t leave the residents alone that I’m going to stuff him in the trunk of an old car I’ve got, drive him to the middle of nowhere where there’s an incinerator an associate of mine runs, and I’m going to fold his greasy little ass up like an accordion and throw him in so he’ll burn pretty.”

Mary could smell the urine running down Havier’s leg.

“I swear on my mother’s grave,” said Havier.

“Your mother ain’t dead,” said Ricci. “You disrespect Mr. Chirac, he’ll have me build a bonfire just so he can roast your balls before he feeds them to that big black cat of his.”

“I understand,” said Havier. “I will not fail you on this.”

“Mr. Chirac told me he knew he could count on you,” said Ricci, “never to bother another patient. Now get working or die. And Havier?”

“Yes, sir?”

“If you don’t show up for work tomorrow, I’ll get some friends together, we’ll find you, and I’ll build that bonfire.”

Havier straightened tall as a Swiss Guard.

“I will report half an hour early, sir,” he said.

“Get back to work,” said Ricci.

Halfway down the hall, Havier slipped and fell, scrambled to his feet again, then went directly to the men’s room to throw up.

Ricci turned to look at Mary.

“You been spying on Mr. Chirac?” he asked Mary.

She started to lie, but knew that wouldn’t work.

“Out of curiosity,” she said. “Only because there’s nothing much to do here.”

Ricci nodded as if he knew what she meant.

“Thing is,” he said, “Mr. Chirac don’t like being spied on. Curiosity doesn’t just kill the cat, Mary. It kills its friends.”

“No.”

“Edgar, my man,” said Ricci, turning his head again to look at the old man. “I got to take you to see Mr. Chirac later tonight, okay? You know what I’m saying?”

Mary saw tears forming in the eyes of her bewildered friend.

“Please, no,” she said, and grabbed Ricci’s wrist.

“Why are you touching me?” growled Ricci.

“Don’t you have a conscience, for God’s sake?” she asked. “He’s had such a hard life. He’ll be lost without me and I’ll be lost without him.”

“That’s nice,” said Ricci, and he blinked only once, his eyelids moving like the curtain coming down at the close of a scene, “but I do what I’m told. You spied on Mr. Chirac, you understand?”

“Can’t you cheat the devil just once? Don’t you have a heart? Take both of us or neither of us. Please.”

Ricci looked at her then looked back at Edgar.

“He’s breathing, you’re breathing,” he said to Mary. “What more do you want?”

“I’ll stop you,” she said.

Ricci looked down at her, smiled, and shook his head. “You sound like my mother,” he said. “She died while I was in prison.”

“You’re mother wouldn’t want you to do this.”

“You’re not my mother. She’s dead. How do you know what she’d want?”

“She’d want you to cheat the devil at least once in your life you coward.”

Ricci turned and walked back down the hall.

“I’ll be back later,” said Ricci over his shoulder.

Mary began to cry.

Mary woke with a start and trying to remember where she was. She was sitting up, she realized. She was in her wheelchair, parked outside of the door to Edgar’s room.

The clock on the wall read eleven fifty five. The nursing home staff had allowed her to wait outside of Edgar’s room. She was about to turn to check on Edgar when she saw that Ricci was pushing a wheelchair down the empty corridor toward the door to Mr. Chirac’s office. Somehow she had slept through him taking Edgar.

“No,” she pleaded, but Ricci kept moving.

He did not even look back.

Mary spun the wheelchair around to follow after him and pulled the rubber wheels around hard.

I can catch him. He’s just walking. I can catch him.

But Ricci had a head start. His broad shoulders and chest obscured most of the chair, but Mary knew that it was not empty.

“Don’t you dare,” she called as she moved down the hallway after them.

Ricci was already at the door. He knocked three times.

Mary was close enough that she heard a silken voice from within say, “Come in, my friend.”

Ricci turned the handle as Mary came to within a few feet of him. She would force herself in before he could close the door. She and Edgar would go together.

Ricci turned his head and the look he gave her stopped her cold. She grasped the wheels and stopped her forward motion.

Ricci looked down at the man in the wheelchair.

Mary followed his glance and saw that it was Havier.

She looked up at Ricci, her eyes wide.

Ricci winked at her, pushed Havier inside, and was closing the door behind him when Mary heard that liquid accented voice say, “Ah, Ricci, my friend, are we thinking for ourselves now?”