The Sheer Magnitude of His Irrelevance

by Ross Pavis

My only mistake was deciding to take the aspirin before hanging myself. I had a headache, and I hated the idea of dying with a headache. I couldn’t take an aspirin without a glass of cold water so I had to let it run a minute to get cold. Meanwhile, the phone rang and I was standing there holding the glass in front of the sink, and the ringing triggered the old Pavlov thing. That was my mistake. I put down the glass, and picked up the phone.

“Jack, don’t hang yourself, I’ll be there in ten minutes, trust me on this.” Click. The water was still running so I went back to the sink. Now It was cold. I filled the glass, went back to my bed, sat down and took the five aspirin. I stared up at the noose I had tied to the plumbing pipe that ran across the ceiling. The chair was against the wall and I needed to move it over a little so it was closer to the dangling noose. I couldn’t see any particular reason not to go through with it, though waiting a few minutes would give the aspirin more time to work.

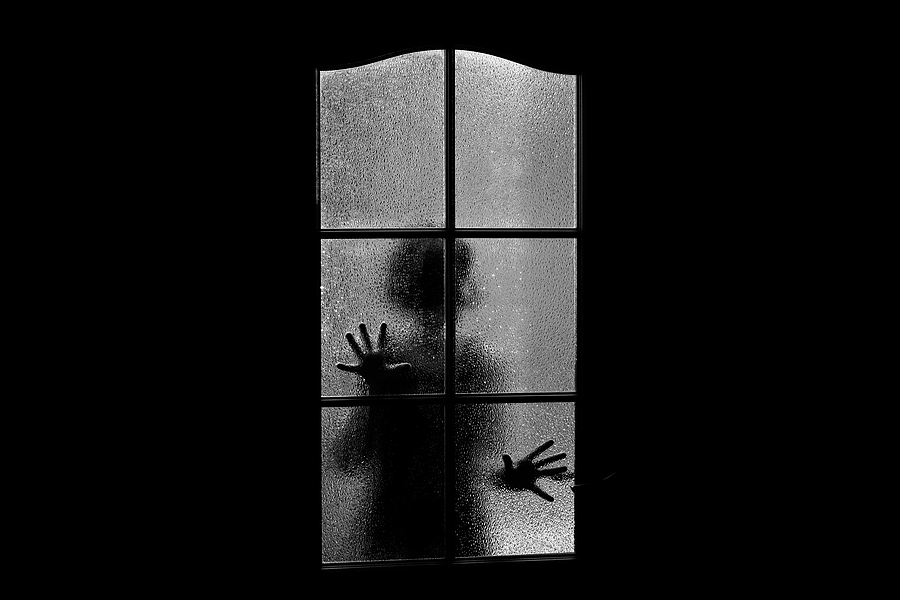

It didn’t seem like a full ten minutes but pretty soon there was a knock at the door which I got up to answer. The man was fairly ordinary looking, though well dressed in a dark grey suit. Not a bad looking fellow, hair nicely coiffed, rosy complexion, around fifty.

“Look, Jack,” he said, in a voice that was surprisingly deep and rather pleasant. “I know everything there is to know. You lost your job, which you hated anyway. You’re broke, you have no savings, no checking, no credit, and you’re four months behind on your rent. And that’s nothing. Your girlfriend left you for your best friend, who was never your friend to begin with, and your family treats you like you don’t exist, which isn’t far off, given the quality of your social life, which has gone from terrible to tragic. And that’s nothing.” He paused for a second, smiled sympathetically, and continued. “You had chances at love and you threw them away. You had your choice of women who offered to share your life and bear your children, and you scorned every one of them. Now there’s nobody left except the mice and cockroaches who scurry across the floor keeping you up half the night as you lie in bed, alone and miserable. And that’s nothing.

“No, Jack, that’s not the worst of it by a long shot, and that’s why I’m here. In your life you have had what we like to call exceptional opportunity – and I’m not just talking about talent here, though of course you had that in abundance. You had much more than that. You had the potential to do good things – scratch that, great things. You could have had a life of spun gold, Jack, a life like an angel, like a fairytale prince who accomplished wondrous deeds and of whom songs are written. It was all right there in front of you, handed to you on a platter, and well… look at where you are now.”

I didn’t see much reason in arguing the point. “Anything else?” I asked. “If you don’t mind, I’ll just place this chair here under the pipe. If you could move a couple feet to the left.”

“What I’m about to tell you may sound a little farfetched.,” he continued.

“Just a few steps further will be fine.”

“I come from a place where everything has been figured out. When I say everything, I mean everything.”

The noose was looking better and better.

“Let me back up a little and explain,” he said. “Think of it like this: if you have what we call complete information, then every contingency is knowable. Get it?”

I just stared.

“Take a field goal kicker who kicks a football. If you know the angle that the toe hits the ball, with exactly how much force, and you know the wind speed and a few other details, you can predict whether or not the ball will make it over the goal post, right? Right. In the same way, if you know everything there is to know about a person, you can make the same kind of prediction.” He winked. “When I say everything, I mean everything. Total life information, every action, experience, emotion, sensation, every detail down to the genome. If you know all that, he’s just like the football.”

“Excuse me, could you move just a little bit more. You’re standing in the exact spot I need to move the chair.” I glanced up pointedly at the noose hanging from the pipe, hoping he’d take the hint.

“Take it one step further,” he continued, ignoring the chair. “All that information, every detail, is recorded and exists forever. All of it.” He was looking at me like he was expecting a reaction, so I nodded a couple of times which seemed to make him happy. “And Jack, you get what I’m saying, right? I’m not just talking about any hypothetical person. I’m talking about a complete record of every single person who ever lived since the beginning of time. Every word, grunt, and sneeze, down to the tiniest detail.”

“Yup, I got it.”

“And I’m not just talking about people. I’m talking about things – every tree, butterfly blade of grass. Every snowflake that ever fell from the sky. It’s all there. You see the implications?”

I looked at him for a second, then I looked up at the noose, then back at him. No doubt about it, he wasn’t leaving until he was finished, so I let out a big sigh, and braced myself for another five or ten minutes.

“Jack, imagine that all this information, the entire data record of history, down to the smallest particle, is readily available; and imagine it exists in a usable, for want of a better word, file. What would you do with it?”

“Delete?”

“What you could do with it is play back different historical events and see what really happened, and why. And that would only be the beginning. You could take it a step further. You could go back and play around a little, make changes, do a little editing – put something in, take something out. Then you could run it forward and see what would have happened if things were a little different.

I was back to moving the chair and finally got it just where I wanted it. I took a deep breath, raised a knee up, and stepped up onto the seat of the chair. He didn’t show any reaction as I reached for the noose and slipped it over my head. He just continued his jabbering.

“You probably don’t see exactly where I’m going with this, but bear with me. When we first saw that the whole thing really worked, it was like being a kid in a candy story. Everyone started asking what would have happened if such and such an event had occurred? You know the types of questions people always ask – what would have happened if somebody stopped John Wilkes Booth, or Hitler, or Lee Harvey Oswald, that sort of thing. Everyone had a different scenario they wanted to try. Just imagine, we suddenly had a way of seeing what the consequences would have been if a single action had been changed or a different decision had been made at any point history – from ancient Greece, to World War II, right up to this minute.”

“There’s a point to this, right?” I asked, as I tightened the noose around my neck like a tie and inched forward to the edge of the chair. He didn’t seem especially concerned as he went on.

“What do you think we discovered?” he asked, without waiting for an answer. “Amazingly enough, we found that if you got rid of an important figure – even one of history’s giants – it didn’t make all that much difference. If you went back and killed Napoleon — oh sure, for a few years there were big changes. This army beats that army. One empire gets bigger, another smaller. But then for some reason, and no one has figured out why, events shift this way and that, and slowly fall back into place. In a few years, almost everything is back to where it would have been if we’d stayed out of it. At first we thought maybe it was a fluke, so we tried it over and over. But the same thing happened every time. Sure, every so often there might be a few minor changes that continued down through the years, but nothing of any lasting significance. When we got rid of George Washington at Valley Forge, hardly anything changes: a sergeant takes over command, gets promoted, and the revolution goes off without a hitch. Two hundred years later, the only changes are a different face on the dollar bill and President’s Day is in October. That’s it. Same thing in politics and the arts, even science. You get rid of Einstein, two years later an optometrist in Rhode Island comes up with the same formula, except instead of E=MC2, he writes it as C2=E/M.” Not as catchy, but it works out to the same thing.”

“An optometrist?”

“Einstein was working in a patent office. You think that makes any more sense?”

It was beginning to look like the only way I was going to get him to keep quiet was taking that last step off the chair. But I had to find out one thing: “Exactly what,” I asked him, “does all this have to do with me?”

He stopped and looked directly into my eyes. “One day, Jack” he said, “almost by pure chance, we made a discovery. For some reason – and it’s almost the opposite of the other situation – there’s some kind of inverse relationship between lifetime failures and monumental historical events. I’m not just talking about ordinary obscure losers. We’re talking people who led lives of agonizing failure – people who, by any normal standard, would appear to be completely irrelevant to the tides of history. And here’s the crux: we found there’s some kind of correlation between a person’s innate potential and the magnitude of their failure. There’s some kind of multiplier effect. It turns out there are a small number of people walking around who were born with extraordinary potential, and yet for one reason or another, every natural gift and opportunity was squandered and ended in failure. These people have what we call a spectacular level of irrelevance, and for reasons still not fully understood, the greater their seeming irrelevance, the bigger their impact on historical events. Ring any bells?”

I was looking at my toes that were hanging over the edge of the chair, moving them up and down. My hands were in my pockets and my body was swaying gently forward, then backward, then forward.

“Jack”, he said, transitioning smoothly from the abstract and back to the situation at hand. “We don’t do this very often. This is an exceedingly rare intervention. You’re almost off the scale. The sheer magnitude of your irrelevance makes it critical that you proceed with your normal life path of complete and abject failure. Events of which you can’t conceive depend upon it. Hanging yourself is simply out of the question.”

The noose was tight. I suddenly realized my headache was gone.

“Come on, Jack, the truth is we already know you didn’t do it. I was much too persuasive, and you lacked the fortitude and commitment. You actually try again in a few years, but by then it’s almost too late because of the – well, best not to know too much. In any case, everything ends up fine; well, not for you exactly, but for history. Just the way it’s supposed to. Come on, hop down, stretch your legs and relax a little.”

I stood there a moment longer keeping the rope taut, pondering his words. “Surely,” I said, “if my miserable existence is so important to future historical events, I should get — I don’t know, some kind of compensation for sticking around? Can’t you offer me something, maybe a stipend of some kind? A little deposit in my bank account? What about a new car? Not even new, pre-owned would be fine.” He nodded sadly. “Look,” I kept trying, “what about a nicer apartment? I’d be happy with air conditioning. How hard is that? Or what about a girlfriend? I’d kill for a girlfriend. It doesn’t have to be for long, a month, two weeks, even a week, for Christ’s sake. That’s not too much for fixing history, is it? Can’t you give me something?”

“Sorry,” he said, shaking his head. “I really am.

“Nothing?

“Nothing,” he said, “it goes against the whole principle. I can only give you the satisfaction that your misery will somehow play a role in the grand scheme in which we all play our part – some big, some small; some happy, some … not so happy. Hopefully that can provide you with some meaning and consolation.”

“Not even a few crumbs of hope? There’s always hope for improvement, isn’t there?”

“You might want to lower your expectations. I suppose I can mention that things aren’t going to be getting much better. As a matter of fact – “

“Any other words of wisdom before you go,” I said, cutting him off. I’d had about all I could take.

“Well, I can you that you should probably cut down on taking so many aspirin. It’s bad for your stomach, and we need to keep you around for a while.”

That was the last I heard from him. A moment later he was gone, gently closing the door behind him, and leaving me standing on the chair in my bare feet, wiggling my toes. I looked at the door, then up at the pipe that supported the noose. Then I looked at the door again. He wasn’t coming back, but my headache already had. “The hell with it”, I said out loud. I pulled off the noose, stepped off the chair and reached for the aspirin.