By

Ferrel D. Moore

Professor Essepi had come aboard that afternoon with five other men. Three were mutes with faces drawn and thin, sunken dark eyes and bald heads, and each bearing a red birthmark on the upper edge of their foreheads that showed from beneath their loose cowls. The mark was shaped like a hand pressed to their skull, as though they had all come forth from the same womb and each was marked by the devil’s touch. Around their necks they wore pewter chains from which hung crossed lightning bolts of an iridescent black metal that shimmered like opal.

“They are priests from the isle of Crete,” Professor Essepi explained to the captain.

When the Captain cocked an eyebrow, the Professor had stared him down. The Professor had obedient hair that seemed unruffled by the breeze. His thin shoulders stooped slightly forward, but his pointed chin aimed forward like a harpoon. He had the eyes of someone called to claim the dead and just a hint of drink about him. The Captain knew nothing about him except that he was the President’s man. He suspected that the Professor had never before set foot on a ship, but since he brought with him papers bearing the Presidential Seal that placed both the Captain and his ship under his command, Captain Baker had nodded as though in agreement.

The Professor had provided the Captain with their destination, as though instructing a carriage driver as to which theater an important dignitary should be driven. Captain Baker had received the directions without comment. It was the third year of war with the Confederacy, and by now there was much that angered him, little that surprised him, and a great deal that he said nothing about.

The three robed figures moved away in unison across the deck, their steps silent beneath their robes as if they floated above the planking. Crewman eyed them with uneasy glances. Several crossed themselves and quickly looked away.

A pushy, persistent wind threw shredded rags of clouds overhead, billowing them like a poor man’s laundry across a cerulean sky of textured Tiffany glass. As the pale sun disappeared behind the clouds, the Professor pulled his collar tighter to his neck.

Captain Baker pretended not to notice.

The fourth man brought on board by the Professor was as tall as the Captain, but with eyebrows thin as a young girl’s. His eyes were copper and flashed like tainted gold when he stepped aboard the ship three steps behind and to one side of the Professor. With hair that hung to the middle of his back like floating strands of black silk, he looked every bit the decadent nobleman striding about to inspect his holdings. He was dressed in a suit the color of a threatening storm cloud and he had a wide mobile mouth drawn below an aquiline nose that was set above his pendulum shaped chin. His cheeks were blushed the color of a wilted pink rose, and his head perched uncertainly on a stalk-like neck.

“And this,” said the Professor, “is Dr. Phineas Slyce.”

“Welcome aboard, sir,” said the Captain with a brief nod of his head.

Dr. Slyce peered at the Captain through silver-rimmed spectacles that balanced on the bridge between his eyes as though teetering on a knife’s edge. His shoulders were only slightly wider than his hips, and the Captain noted that the man’s thin, bony hands hung almost to mid-thigh.

“Where may I put my valises?” inquired Dr. Slyce, as though he were addressing a porter. Two quilted-cloth bags with metal braced sides and bottoms hung from each hand, each filled to the point of stretching.

“Cherney,” said Captain Baker, “take the man’s bags and show him to his berth.

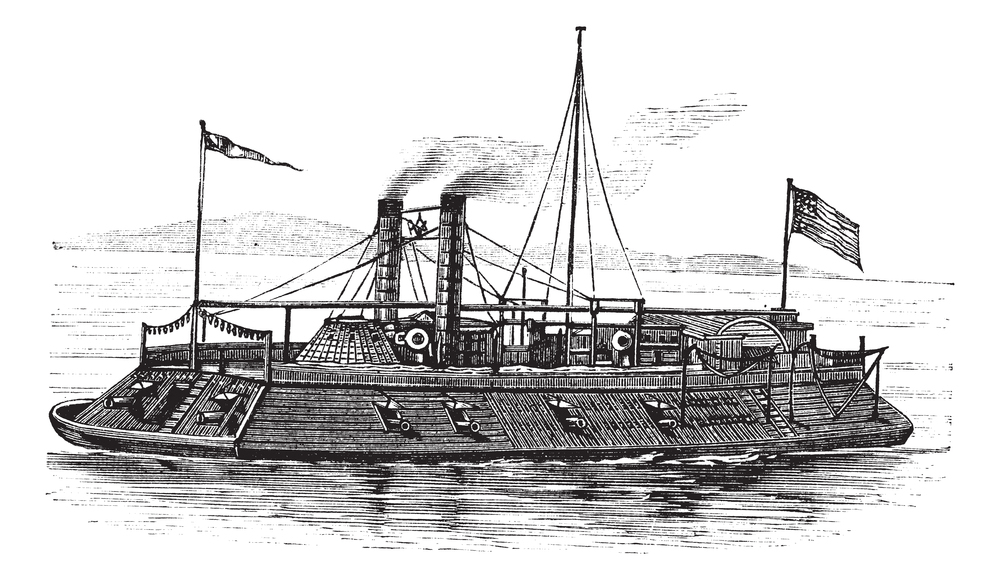

“Aye, aye, Captain,” answered Cherney, as though carrying a passenger’s bags were an everyday occurrence on an ironclad ship.

Dr. Slyce set his bags down on the deck. An odd-shaped ring flashed on the man’s hand as he did so. Although it appeared to have been wrought from fine gold, it reflected the day’s bright sunlight as though it were a distorted prism. The First Mate, a Portugese that the Captain called “Mr. Abilio,” noted the ring but turned away from it after a momentary stare.

“Thank you, sir,” he nodded.

“That would be Captain,” scolded Cherney.

Cherney was just less than six feet tall, with shoulders as wide as a cabin doorway, anchor chain arms, and a flat face ringed with a bristling brown beard. He stepped forward and grasped the bags by their metal handles and lifted. The bags rose up an inch, and then fell back to the planking. Still bent over, Cherney raised his head to gawk at the thin man who looked back at him without expression.

The sailor moved to crouch between the two bags, then began to straighten, this time lifting with his legs. His shoulder muscles tensed and bunched with the effort. His face flushed and turned red as a metal pan heating over a fire. The bags rose an inch, and then two. Cherney’s body began to shake and his knees wobbled in and out as though he were about to collapse. The bags rose another inch, then yet another, then they dropped from the sailor’s fingers and crashed to the deck. Still bent over, Cherney looked at his hands as though they had turned traitor.

Captain Baker looked from his man to the slender figure of Dr. Slyce, then back at his man again. Cherney screwed up his face, stood, and took a step toward Dr. Slyce.

“Mind your temper,” warned the Captain.

Cherney whirled to face him. “He must have a brace of anchors in those things, Captain.”

Dr. Slyce brushed past the sailor, stood between the bags, then picked them straight up again. “I will follow you now,” he said to Cherney.

As the doctor followed the defeated Cherney, other sailors stared at him as though a wild animal had been brought on board.

“I’ll tolerate no dallying,” snapped the Captain to the gawkers. “Mind your duties.”

“Dr. Slyce,” explained the Professor, “is my assistant.”

“Is that so?” arched the Captain.

“Yes, quite,” said Professor Essepi.

“And you sir?”

“I am a trouble-shooter, for want of a better description.”

“A trouble-shooter with a Presidential order giving him command of my ship,” sniped the Captain.

“Indeed,” said the Professor. “It helps to have connections.”

It was the Professor Essepi’s fifth man that caused the most commotion. He was carried on board slung from a pole by his ankles and wrists by two Union Army soldiers and wore a convict’s linens. A drawstring pulled into a knot around his neck cinched a black cotton bag over the prisoner’s head. Beneath the hood, the Captain thought that the man must yet be gagged, though it did little to muffle the hideous wails and screams that rose from him as from seagulls denied food.

As they carried the bedlamite past him, Professor Essepi’s jaw tightened hard enough that the Captain saw a drop of bright red blood form at the corner of the Professor’s mouth.

On their second night at sea, Professor Essepi sat across a bench from Dr. Slyce. The doctor had earlier made a point of opening the small cabin’s door to search back and forth for sailors with too keen an interest in the Professor’s business. When he had satisfied his curiosity, he ducked his head to re-enter the room, came in and then sat down and spoke. He averted his eyes from the flask and cup that sat on the bench between them.

“You will have to tell the Captain something. He’s getting nervous,” Dr. Slyce said, “and the men say that the madman will bring them disaster.”

The Professor laid aside his journal and took off his spectacles. Using a clean handkerchief, he scrubbed them clear of coal dust with a fastidiousness that a jeweler would have admired. He then placed them in a pocket-case and slid them into his coat and drank down the last of the whiskey in his cup. With his head tilted back, he tapped the side of the metal to coax out the last, the very last drop. As he returned it to the bench and poured half a finger into it, the Professor ran his tongue over his lower lip as though to savor the numbing sensation of his last swallow.

“Some of them are shoveling coal in the belly of this filthy ship,” he then said. “Others clean and oil cannons while their mates scrub the grime from the decking and the armor plating. The air is so filthy it’s a wonder we can breathe at all.” The Professor grimaced. “When they are not cleaning,” he continued, “ they are either patrolling empty stretches of ocean or being shot at by Confederate cannons. Their lives are misery and I do not care. You know well enough why we’re here and how important it is to me.”

The liquor in the cup seemed to fascinate the Professor. He angled his head from this angle to that as he spoke, sliding his shoulders from side to side as he did so like a cat preparing to pounce on a mouse.

“How close the two of you are,” said Dr. Slyce as the one side of his mouth peeled back slightly in a tiny sneer. “One insane, and the other trying hard to follow.”

As though he were smoothing sculpting clay, Dr. Slyce ran his hands over and through his hair, then stretched wide his long arms and yawned, revealing rows of amber colored sharp little teeth that glowed like phosphorescent fungus in the dim light. The Professor suppressed the desire to shudder whenever he saw them.

“I know that you have no care for the morrow, or your estates,” Dr. Slyce continued as his hands dropped to his knees. He leaned forward and said in a soft delighted voice, “But only for this one deed. That is all that concerns you. But listen to me, my inebriated friend— great tumult closes in on us. We are at sea holding a metal pole while heat lightening crackles the night sky.”

“You sound like a bloody prophet of doom,” shrugged the Professor. “These men can take care of themselves. I have instructed the Captain that the decks are to be patrolled both day and night. We have done what we can and that is enough. It means nothing to me anyway unless we can save Secretary Marshall’s son from his madness. He now hangs in manacles and chains in the brig chattering like a monkey. The Secretary of the Navy has gone mad. So damned what that his parents and brothers and sisters are dead? So damned what if his sole remaining relative acts like a primate and screams all night that the monsters are coming. Is that enough to drive a man over the edge? Considering that I am confidante to a lunatic with a bedlamite for a son, is it any wonder I bloody well drink all the time?”

The place where they sat was a storage room that Professor Essepi had commandeered for their use. Wooden crates of this and that had been stacked in each corner to allow them room to sit on the two remaining crates that had been conscripted into service as stools. The Professor’s nose filled with the greasy odor of stale wood and the coal dust that seemed to hang suspended throughout the air of the entire ship. He saw Dr. Slyce bring his hand up and rub his chin.

“The influence you will have,” chided Dr. Slyce. “When we are successful— when we have returned his son to his right mind— then anything you ask for, Secretary Marshall will be compelled to give you. All of the gold that your family has given to fight slavery—”

“Bollix slavery. Let the slaves fight for themselves or keep picking cotton. We’ll win this war and my dear father’s business will take back our investment with usurious interest from the South.”

“Your just rewards,” affirmed the doctor with a sly wink.

“Until then,” said Professor Essepi, “I drink.”

“And what will you tell the Captain tomorrow?” asked Dr. Slyce.

“Don’t worry,” continued Professor Essepi after he leaned back his head again and craned his neck as though to feel its smoky warmth burn its way down his throat. “I’ll be sober enough to think of something by then. ”

A determined smile spread across Dr. Slyce’s face like a sliver of yellow moon breaking free from behind grasping cloud hands, and he said, “It is the why that will shock him.”

“I don’t care a whit if the very idea kills him,” said the Professor. His head slid forward just a tiny bit, as though he were nodding off to sleep. “As long as he takes us first to the spot where this thing of yours will come up out of the water—. ”

“The Eye of Dagon,” added the doctor helpfully.

One eye popped open and Professor Essepi glared at him through it. “You are enjoying this,” he said as he opened his other eye, lifted his chin, and glared at the man who towered over him even when they were both seated. “How would you enjoy it if I instructed the Captain to throw you over the railing? I have that authority, you know.”

“But who then would perform the ritual?” asked Dr. Slyce.

Professor Essepi grinned and took hold of his tin cup and swirled the last of the whiskey it held in loping circles as though he were a chemist manually stirring a laboratory flask.

“What use is power if one never uses it?” asked the Professor.

The ship groaned as though pained but then fell silent.

Professor Essepi looked up at Dr. Slyce.

“What was that?” he demanded.

For a moment, Dr. Slyce appeared to consider and then answered, “The ship is afraid. The ship knows our destiny.”

“Save your claptrap for the superstitious sailors. I swear I’ll tell the Captain to throw you straight away over the railing and into the sea if you keep provoking me. I don’t care if it takes twenty or thirty men to do it. You may be a foot or so taller than the rest of us and three or four times as strong, but you are only a man after all.”

“Remember those words,” whispered Dr. Slyce.

There was silence for a moment, and the Professor could feel his mind suffuse the amber state of indolence gifted to a drinker by good whiskey. His disconnected thoughts hovered about the image of Secretary Marshall’s son chained to the brig’s rough planks.

“Can you actually restore his mind?” asked Professor Essepi, who fell back against the wall as he said it and stared up at the ceiling.

“You doubt me? I can guarantee that if we find the Eye of Dagon, then I will fully restore Secretary Marshall’s son to his former self. You have brought the priests to me using the so great power of your government, and transported them to be here with us on this voyage. Without the direct appeal of your President, they would never have left their island. Now that they are here, their continued chanting day and night will strengthen the Secretary’s son for the moment when I can restore his sanity. I cannot repair his eyes,” he mused, “but I can restore his mind.”

“Tell me again why I believe that you can perform this miracle.”

“Secretary Marshall’s son saw something here, out at sea, that drove him completely mad,” said Dr. Slyce. “I will prove that to you, restore him to his senses, and you will never disbelieve or doubt me again.”

The oil lantern fueled a furtive orange-yellow flame that smoked its glass shell housing. It sat between them on the flat bench that they were using as a table, and with each flicker of combustion it sent furtive shadows skulking around the room. The odor of its burning was lost in the oily coal smell that seemed to emanate from the ship’s very beams. But the light that emanated from it flickered in the doctor’s eyes.

“Consider what I have already told you. Each time in the past that this has occurred,” continued Dr. Slyce, “the ships were left behind untouched, just as now. Only the men were taken or driven mad. Remember the Sirens of the ancient Greek Mariners? There are many legends from many traditions. But in the Elder Gods, we see such legends at their most terrifying. Remember, when the Eye of Dagon rose but did not see the sign that it sought, madness and death descended on anyone that it looked upon. The Secretary’s son perhaps saved his life by putting out his own eyes.”

“Poor bastard,” shuddered Professor Essepi.

“As far as I know, the he is the only man who has ever survived such events since the incident I came across in the Mediterranean. That was nearly twenty years ago. But these events occur over and again in cycles going back as far as written history extends. I have been chasing this phenomenon for the greater portion of my adult life. But here, let me recount this quote for you from the records I am translating— the Eye of Dagon rises and claims his creatures each third cycle of the Red Moon. If the Eye of Dagon rises and sees the sacrifice, then he shall pour out his words through the son of Lyssa and Dagon’s hordes shall come forth to reclaim the seas with he who performed the sacrifice as his priest among men.”

“What does that mean?” asked the Professor.

“Listen to me, my friend,” said the Doctor. “I have spent my entire life searching the darkest, wildest seacoasts of this earth to construct the history of such events. I am a pariah among my colleagues. Universities shun me. No one would dream of publishing my findings. My degree is useless to me since I began this obsession to know the ways of ancient secret societies, to learn all I could of their Elder Gods and their powers. I follow this labyrinthine path for my own satisfaction and since you are making it possible for me to see what no one else has ever seen and survived, I am in your service.”

Professor Essepi nodded as though weary. It went without saying that Sr. Slyce had an agenda of his own, but the Professor’s whiskey flask was almost empty, and that transcendent catastrophe eclipsed the Doctor’s machinations.

“I’ve told you before, doctor. If those priests and your ritual can return him to sanity, not only the Union and the Confederacy can go to damnation, but I will be in your debt.”

The flame of their lantern was an unsettled spirit, and for an awful moment, Professor Essepi thought he something blink in the depths of the doctor’s eyes.

On their third day at sea, Professor Essepi was up and on deck early, his peacoat buttoned to the neck, and his beret pulled down almost to his ears. Peculiar dreams had woken him twice during the night. After toweling away the night sweats that had coated his skin the way the grimy smoke from the coal furnaces that coated the guns and the ship itself with oily black grit he had lay back down and closed his eyes, trying not to remember the dreams. After a while, he felt his consciousness growing numb as he passed through the hypnogogic prelude to sleep. He felt his muscles relax and jaw loosen and he was almost somnolent when he had heard the five a.m. bugle blow.

“Good morning, Professor,” said Captain Baker.

The Professor clapped his hands together, and then rubbed his eyes. He took in the morning deck swabbing with what little light there was and then glanced around as though making an inspection. There were sailors polishing brasswork and others burnishing the metal framings where the gun carriages rotated. The First Mate was shouting orders at those swabbing the deck, and the Professor shook his head in amazement.

“Must they do this every morning?” he asked as he sniffed the air.

Captain Baker said, “On board a ship, discipline is everything. Saltwater and coal dust, sir, are like locusts that eat away everything on which they land and we must battle them each and every day.”

The morning sun rose slowly out of the ocean to the east, an eruption of saffron brilliance at the edge of an ocean garden draped til then in violet blackness. The morning air was brisk, but whatever scents the sea air carried were lost in the sulfurous smell of burning coal and cleaning oil.

“Yes, well I can see why you have to have someone run around the decks shouting to roust them awake.”

The fuzziness had yet to clear from his brain after last night’s drinking. He decided to wait until after lunch before his next swig.

“I expect them out of their beds and on their feet, then on deck with their hammocks lashed within ten minutes of the morning bugle. You find the schedule difficult, do you? Within a week, you’ll be used to it.”

“Never,” swore the Professor.

“I must ask you,” said the Captain as he crossed his hands behind his back and looked straight ahead, “do those priests of yours pray all day and all night? I have reports that they pray or chant or whatever they do without respite. At times, the men say that they are near wailing. Have them restrain themselves, Professor. Sailors are superstitious. This is causing unrest.”

Professor Essepi wrinkled his brow and stroked his slight moustache, twisting the right tip between his fingers as though it were the end of an artist’s paintbrush. He tilted his head forward, and then cleared his throat.

“Perhaps,” he said at last.

“And I thought they were held to a vow of silence,” tested the Captain.

“In their religion,” replied the Professor, “chanting is not speaking. According to Dr. Slyce, they may chant their litanies all day long for that very reason— to keep them from speaking.”

“I see. Well, my men have reported strange noises from their quarters at odd times during the night,” added the Captain.

“Strange noises?”

“Yes. Strange noises.”

“Such as?”

The Captain kept his eyes locked on a point fixed on the far away horizon as he replied.

“They couldn’t say. One thought he heard a child cry out.”

“A child? On board your ship? You have allowed a child on board during this mission?”

“There are no children on this ship,” thundered the Captain as he turned to face the Professor. High color had bloomed in his cheeks, and his eyebrows had pulled together like a snake preparing to strike.

“Yes, well,” said the Professor, “since you say there are no children on board, then I should say that your seaman are to such give such strange noises no mind,” said the Professor. He looked straight at the Captain; his chin lifted just enough to meet the master of the ship’s eyes.

The Captain was the taller of the two by a matter of three or four inches. His frame was solid as a ship’s hull. He displayed a full black beard that looked glued around his heavy jaw-line as though in imitation of Mr. Lincoln’s own. His eyes were light gray. Like the mast of a sailing vessel, his posture was straight and tall.

Professor Essepi stood shorter than the Captain. With hands jammed in his blue pea coat pocket he stood easy as though he were a man accustomed to the motions of an ocean-going vessel although it was in fact his first such voyage. His face was slightly blushed by the constant ministrations of sea air and sun, and his eyes pulled away from the open waters and focused on things within walking distance.

“I see,” continued the Captain. “Then can you at least tell me if these men ever eat? They have requested no food nor do they ever show their faces at mess.”

“They are island men and unused to such close quarters. It is natural for them to keep to themselves,” said the Professor. “Yet since they are men such as you and I, and yes, they must eat. There is a logical explanation. They have brought with them their own food. It’s a gruesome smelling braid of dried vegetables and herbs. They keep it coiled like a rope about their waist. But that and water are enough to sustain them. Is that quite your last question on the topic?”

After taking a breath and exhaling quite slowly, the Captain asked, “Will you tell me now why they are here?”

“No.”

“Will you tell me why the skeleton with the strength of Hercules is on my ship?”

“No.”

“I ask you again,” said the Captain, his voice rising with frustration, “when can you tell me what this is all about?”

“Soon. You must remember that I am acting under the direct orders of the President of the United States, as are you yourself.”

“Then will you at least tell me, sir, why a blind madman is here on my ship, manacled and chained in my brig? Even the cook crosses himself whenever that bedlamite is mentioned. My men are simple and superstitious. None of them will dare speak out to Mr. Abilio or myself, but they expect disaster. They believe he brings with him a curse. For my own piece of mind, at least tell me why you brought him aboard my ship.”

The outlines of the Captain’s face were sharp edged, and his eyes caught the glint of the rising sun. The Professor guessed that the man’s tendons were tightening like piano wire pulled taught by the twist of a key, but there was nothing to be done for it yet.

“Because,” said the Professor, “he is my madman.”

Of the members of Professor Essepi’s party, only the Professor himself seemed to sleep. The Priests continued to chant in their makeshift quarters. Their sonorous litany seemed to vibrate the very atmosphere of the ship as though a long bow were being dragged across a thick catgut string. By the fourth night, the crew has taken to plugging their ears with candle wax to keep the sound from affecting their nerves.

Because he was a member of the Professor’s party and therefore had the run of the ship day or night, the crew soon became aware that Dr. Slyce walked the ship’s decks at all hours, at night scanning the dark waters of broken blue-black glass that stretched on all sides as though looking for a friendly face.

On that fourth night, as the coal burners flared the darkness and occasionally spent spectacular showers of sparks into a night sky as oppressive as the underbelly of a leviathan, the ocean air began to smell faintly of decay. Dr. Slyce was actually craning his head over the bow railing, as though the amaranthine whisperings of the ocean were speaking to him.

“Do you miss the land, Dr. Slyce?” asked Mr. Abilio.

Dr. Slyce jerked his head up and turned to face the First Mate.

“My apologies if I have startled you,” said Mr. Abilio.

“I was, how do you say, hypnotized by the sea.”

“Of course,” said Mr. Abilio.

With a casual flick of his wrist, Dr. Slyce took in the boat. “I am unused to being approached with such discretion,” he said. “But you are a seaman and I am not. It is easy to startle a man not in his element.”

“I’ll keep that in mind,” said Mr. Abilio. “And you be careful, too, doctor. It’s easier than you think to fall overboard. No one would ever know what happened to you.”

The doctor’s head swung from side to side to see if they were indeed alone.

“Why do you prowl these decks at all hours of the night?” pressed Mr. Abilio. “Can you not sleep?”

Dr. Slyce turned and scanned the sea. Then looked again at the First Mate. “I see,” he said with a thin smile, “that you always carry that impressive knife with you. May I perhaps examine it?”

Mr. Abilio held the much taller man’s eyes. In point of fact, if he had held his own head level, he would have been staring at the doctor’s sternum.

“In my country, in my home port, we value our knives more than our women. My answer, therefore, is no. And I ask you again, doctor, have you some difficulty sleeping? Perhaps the professor could share some of his whiskey with you.”

“There truly are few secrets on a ship,” observed the doctor for the second time during the voyage.

“You need your sleep,” said Mr. Abilio. “Seamen are greedy for their sleep.”

“Sleep flies,” the doctor said through barely parted lips, “in the anticipation of power.”

A rush of wind blew across the ship like a dying gasp.

On the afternoon of their fourth day at sea, Professor Essepi met with Captain Baker in the Captain’s quarters.

“Captain?” said Professor Essepi in a low voice. “I am now ready to divulge the nature of our mission to you.”

Captain Baker’s brow compressed into three thick folds of skin brushed with an oily dark sheen. His eyes bulged slightly as though pressure were building inside his head as it did in the ship’s boilers, pressing them forward from their sockets. His dark hair glistened in the lamplight as he rose from his chair.

“It’s about damned time,” he growled.

“Seven ships have disappeared in three months,” began the Professor, “and the Secretary of the Navy is a man of terrible temper in the best of circumstances. But seven ships— even the President himself is demanding an explanation.”

“In these waters?” demanded Captain Baker, and he waved his hand toward the circle of glass behind his head.

Professor Essepi shrugged. “We believe so.”

“Gone without a trace?” asked Captain Baker.

The ship creaked all around him, like a horse testing the confines of its stall.

“No,” answered the Professor.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that each of the ships were found within a few weeks of their disappearance.”

“And the crew?” asked the Captain.

“Gone,” acknowledged the Professor.

“Explain yourself.”

“There’s little to explain. The ships were floundering, untended by human hand.”

“Untended by human hand?” sneered the Captain. “I suppose you mean something by that?”

Professor Essepi stood, almost as though the Captain’s jab were his cue to rise to a podium and lecture a class of freshmen.

“I’ll take some of your whiskey first, if you please,” he said.

“I should have you manacled right beside your lunatic,” said Captain Baker.

“That would mean you would have a lot of explaining to do at your court martial,” said the Professor.

“I despise men like yourself,” said the Captain.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Your fight your wars from behind your desks, while the rest of us man the front lines.”

“Careful, Captain. I realize that you grate under the yoke of my authority, but you do not wish, I assure you, to figure prominently in the report I file when we return to land.”

Captain Baker grunted, then took out a flask and two cups and poured a finger’s worth in each. He slid the one in Professor Essepi’s direction, and lifted his own to his lips.

“A toast,” said the Professor.

“To the deep,” replied the Captain and drank his down in one swift inhalation.

“And to its secrets,” added the Professor, and he did likewise.

“Time to fess up, Professor,” said the Captain.

Professor Essepi ran the back of his hand across and set his cup back on to the Captain’s desk. The familiar warmth of whiskey would soon spread throughout his body.

“Right,” he said. “Each of the ships was raked with what seems to be claws.”

The Captain raised an eyebrow.

“Claws?”

“Like those of a bear.”

“A seagoing bear, I suppose?”

“Laugh if you will,” said the Professor. “I’ve seen the gouges. And I didn’t say a bear. I said like those of a bear.”

The Captain waived a hand. “Go on,” he said.

“And on each of the ships we found markings carved in to the railings. They’re etched in some sort of glyphic language that we can’t decipher.”

“Glyphic language?” laughed Captain Baker. “And what is that supposed to mean?”

“Like the symbols on Egyptian tombs,” said the Professor. “Only, there is something queer and disquieting about them. No one is able to look at them for any length of time without getting nauseous and even developing a sense of vertigo. Quite unusual. I’ve had entire sections of railing containing the symbols cut away and placed in protected storage.”

What the Professor did not share with the Captain was that three of his workmen had gone mad within days of examining the symbols, and that only Dr. Slyce seemed to be able to look at them with impunity.

“Claw markings and Egyptian symbols? That’s quite a lot of rubbish you’ve brought aboard my ship, Professor Essepi. What I want to know is what we’re here for and what sort of danger to expect. You may well command this mission, but I still command this ship and the lives of everyone on it are my responsibility.”

Professor Essepi reached across the Captain’s table and poured himself another drink.

“All I can tell you,” he said, “is that the madman whom you have manacled in the brig was the only survivor found on any of the ships. The priests— whose peculiar chantings you have never ceased to complain about— are perhaps our only chance to regain his sanity so that we may learn what transpired when his vessel was attacked. The Secretary of the Navy, whose son we are referring to, is the only man who can tell us whether it was by the Confederate Navy or sea monsters. Secretary Marshall believes it was perpetrated by the former, while Dr. Slyce believes the latter.”

“I don’t trust that man,” muttered the Captain.

“The Secretary?”

“Your Dr. Slyce. I’ve had Mr. Abilio keep a close watch on him, and I don’t like what he reports.”

Professor Essepi drank down the entire contents of his glass.

“Let me worry about Professor Essepi,” he said.

It was the fifth day at sea and the late afternoon sky was the color of coal marks on an old shovel when Dr. Slyce carried word to the Captain that the Professor had requested his presence at the ship’s brig. From the corner of his eye, the Captain saw sailors casting furtive glances his way. Dr. Slyce was viewed with the same distrust and suspicion that the men felt toward each of the characters that the Professor had brought on board with him. Word as to the man’s prodigious strength and humiliation of Cherney had spread throughout the ship. Certainly his unusual appearance had contributed to the rumors that had risen around him like smoke from smoldering leaves. Before Captain Baker could answer, Dr. Slyce turned heel and began walking away.

Although the Captain would have liked to tell Dr. Slyce that it was his ship and he would go where he chose when he bloody well chose, he instead called after the man’s back, “Tell the Professor that I will be along shortly.”

Dr. Slyce kept walking. His boots clapped along the deck making a sound like a horse walking through a stall.

The sky overhead was clear and crisp. The smell of the sea co-mingled with that of the stacks, and they were making good time. Yet, the helmsman had just reported that the compass needle was swinging this way and that as though the imp of the perverse had taken control of it.

“It’s not unheard of,” the Captain said to Mr. Abilio, who was watching Dr. Slyce disappear.

The Portugese, a man who had just barely met the five foot five inches requirement of the Union Navy for being a sailor, said nothing. His thick, greasy black hair stuck out from beneath his cap. Mr. Abilio’s face was pockmarked, and a long thick scar squirmed down his face from high on his cheekbone down to his chin like a languorous snake, and his dark eyes opened only a little wider at the Captain’s remark.

“No one knows what causes these irregularities, but see that the navigator makes a record of it,” continued the Captain.

What the Captain did not say, but that both he and Mr. Abilio both knew well, was that such irregularities had never before been heard of in the waters that they prowled.

“Do you have something on your mind, Mr. Abilio?”

“Last night sir, a sailor on watch reported seeing Dr. Slyce drop something over the bow railing.”

The Captain did not turn to face him, but his face tightened.

“And what was it that the good doctor was ridding himself of in such an unusual manner?”

“Seaman couldn’t say, sir, but he told me with a little prodding that it looked like a child’s tombstone.”

At that, Captain Baker turned to face the first Mate. “Like a child’s tombstone?”

“Yes, sir,” confirmed Mr. Abilio. “About that size. Shone like white marble. Not saying it was, but that’s what it reminded him of when he saw it. He took it from his bloody bag and dropped it over the edge like it was a piece of wood. If it was marble or something like it, then it’s small wonder Mr. Cherney couldn’t lift the Doctor’s bags.”

The Captain, his face tight as a twisted rag, considered this for a moment.

“And did the sailor approach him about this?” asked Captain Baker.

“No sir. As you instructed, I’ve told the men that the Professor and his people have the run of the ship and, if I may be frank, Captain, there’s not a man on board that’s not terrified of Dr. Slyce.”

“You weren’t including yourself or myself in that estimate, were you Mr. Abilio?”

“No sir, I wasn’t,” answered the first Mate.

“Remember this, Mr. Abilio,” said the Captain, “men who drink choose bad enough companions, but men who drink and are privileged choose worse. Do you understand?”

“Certainly, sir.”

“Then I’ll be attending to the Professor.”

Captain Baker could feel the eyes of the Portugese on the back of his neck as he turned to follow in the footsteps of Doctor Slyce.

As the door swung closed behind him and his eyes adjusted to the dim light, Captain Baker saw Professor Essepi reach for the swath of bandages that covered the upper half of the madman’s head. Were it not for the chains and thick iron bracelets that secured the man to the wall, the scene might have been that of a doctor ministering to a patient.

After a moment of fumbling with the knot, Professor Essepi unwound the dark cloth from the soldier’s head. His back blocked the Captain’s view of their prisoner, but when he stepped away, Captain Baker jerked his head back in surprise. The man’s eyes were gruesome holes rimmed by crusted, enflamed scar tissue.

“Self-inflicted, we presume,” said the Professor, wiping his coat sleeve across his forehead to clean away beads of perspiration.

Before the Captain could respond, the bedlamite opened wide a mouth full of broken teeth and shrieked, “It’s coming, it’s coming.”

The man’s cry was a pistol shot fired too close to Captain Baker’s ear. The Captain jerked his head back with such force that he cracked it up against a support beam. The prisoner’s head fell then forward on his chest, and his body began to saw from side to side on the narrow wooden bench.

“What is he saying?” demanded the Captain in a hoarse whisper, paying no attention to the tender spot on the back of his skull. “There’s nothing for him to see, he’s blind. He has no eyes.”

“The Deep,” croaked the blind man as though it was his last breath. “Rising from the Deep.”

Professor Essepi shook his head. “In between ravings, he’s been repeating the same thing over and again since the day that we found him.”

Spittle formed at the corners of the prisoner’s mouth, and, when the Professor saw it, he dabbed it away with a deft dabbing motion like that of a parent cleaning a child.

“And you say this is Secretary Marshall’s son?”

“Yes,” continued the Professor. “So far as we know, he is the only living survivor of whatever has been happening at sea.”

Professor Essepi began stroking the man’s thin brown hair. The soldier’s head began to loll, but his whole body continued to weave gently from side to side as though to rock himself to sleep.

“What did this to you?” the Professor whispered to the man. “What did you see that so damaged your mind? What did you see that turned you into a madman?”

“This is difficult to believe,” said the Captain.

“Quite,” said Professor Essepi without looking around.

“And you think these priests that stay locked in their quarters chanting and making such hideous noises can actually help this man?” asked Captain Baker.

“So says Dr. Slyce,” murmured Professor Essepi. His voice rose and faded away like a departing train whistle.

While the Professor Essepi and Captain Baker were sequestered with the bedlamite, Mr. Abilio located Dr. Slyce. The cadaverous man was dressed all in black, and stood once again looking out at the ocean with his hands resting on the railing.

“Here you are again,” he said.

Dr. Slyce appeared not to notice him.

“The men have asked me why each night you drop things into the ocean.”

“It is an ancient custom,” Dr. Slyce said without looking around.

“Is that so?”

“From times long ago before you were born.”

“You sound as though you were there,” said Mr. Abilio.

“I come from a very old family.”

“And is there a purpose to this ritual?”

Dr. Slyce turned and pulled himself up to his full height.

“Did you know that in times gone by, my friend, it was believed by some that a race of Elder Gods lived beneath the sea? Did you know that those who followed them and became like them were believed to be immune from the ravages of disease and death? No? For a seaman, Mr. Abilio, there is really a great deal that you do not know about the sea.”

“The things you drop over the side each night?” prodded Mr. Abilio.

“Gifts. Offerings. Entreaties. In terrible times, it is well to be on the side of power.”

That night, Dr. Essepi sat alone in his quarters and drank. He lay in a hammock that swayed with the ship’s gentle rocking and thought of what the Captain had said to him earlier.

“Fight from behind a desk?” he spat. “Why not? Why bloody not?”

His vision blurred and the room became a hazy gauze of plain colored wood colors and the persistent heat that rose from the coal fire that blazed away below caused sweat to creep surreptitiously from the pores of his forehead. Above the ship’s noises he imagined that he heard the droning of the priests, chanting every waking moment of their lives to turn away chaos and restore clarity. Stupid bastards, each and every one of them. Wasting their lives in the cause of the religion.

“What if your God is insane?” he yelled and immediately began to laugh so hard that he had to struggle to keep from tipping out of his hammock.

By the fifth night, the seas had grown rougher, and the air was thick with the odor of sulfur. Near nine bells, a faint stygian mist rose from the water like an evil steam. Captain Baker and Mr. Abilio leaned over the port railing to stare at the phenomena. Fear of the Captain’s wrath kept the sailors at their positions, but by the time that Professor Essepi and Dr. Slyce had joined the Captain and Mr. Abilio, the discourse among the crew was increasing in volume. With the compass so erratic that they could not depend on it at all save for a source of perpetual motion, they had been navigating by the stars. As the fog grew in volume and density, the horrified men saw it smear across the heavens like smoke from a smudge-pot and quench those stars until, one by one, it had erased them from the heavens. Before their stretched-wide eyes, the sea began to slowly bubble and boil.

“Lord Jesus, save us,” said Mr. Abilio.

Pale red moonlight shimmered across restless waters black as tar, and a gangrenous smell rose with bubbles the size of kettles that domed and broke with a foul hiss. The bloated bodies of silver colored fish bobbed and fell as though trying to right themselves. Dark wisps twisted free from the sea and rose high into the night like spirits released from a watery tomb.

“We’re into it now,” said Captain Baker.

“Into what, Captain?” asked Mr. Abilio.

“The Devil’s own lair,” answered Captain Baker.

The foul fog embraced the ship, and soon those aboard the USS Vincent could see no farther than three feet clearly in any direction. Beyond that, it was like looking through gauze.

Professor Essepi grasped Dr. Slyce’s coat sleeved and gasped, “It’s happening.”

The doctor leaned forward and hissed, “Tonight you will have to stand on your own. I have other business.”

In the peculiar colors that were that night, Professor Essepi’s eyes were so dark that it was as if they had collapsed inward. He had only been drinking for the last several hours, but already his sense of balance was tenuous.

“But it must be time now, time to save the boy,” persisted the Professor, clinging to Dr. Slyce’s elongated sleeve.

“It is my time now,” spat the doctor. “Thank you so much, Professor, for making it possible. But it is now time to part ways.”

“But the bedlamite, what about the bedlamite? Can’t he now be cured?”

With sailors pressed together staring over the railing, no one seemed to notice as Dr. Slyce grabbed the Professor and pulled him by the hair so that he could position his mouth next to his ear and declare, “Madman are madman— there is neither salvation nor cure for them. Good bye, Professor.”

A fireball ignited fifty yards from the ship. Concussive heat roared across the surface of the water as though a gate to Hell had swung open. Men turned and dove face down against the ship’s planking and some rolled against the iron armor plating, clapping their rough, work-edged palms over their ears as they slammed against the deck.

“Methane,” yelled the Professor from beneath the tarp covering his face. “Shut down the boilers and have your men put away all firearms.”

That said, Professor Essepi’s stomach lurched and he vomited. In the miasma of smells that now haunted the deck of the USS Vincent, he could scarcely smell the odor or taste the residue in his mouth. Nonetheless, he wiped his mouth with his sleeve.

“No guns?” winced the Portuguese.

“Why not?” demanded the Captain.

“A spark or a static discharge could set the methane gas off,” said the Professor as he raised himself to his feet and clutched his abdomen. “It’s that bloody awful smell. There is something that mixes with the methane to give it that stench. The whole mixture is bubbling up from the ocean itself. A spark will cause this whole ship could go up in flames.”

Sailors and officers alike stood transfixed by the anarchy that roiled the waters around their suddenly too small ironclad vessel. They were adrift without navigation in an anarchous ocean of madness.

The air convulsed with the sound a mighty roar like a maelstrom rising from the pit. The night was lit with grasping fingers of fire that reached up from the water to flash into fireballs like incandescent mushrooms and the men gasped as a fountain of water shot up fifty feet into the air like a shaft of ocean fury. Atop it crested something dark and oily black-bright.

When the water column smashed back into the sea, the impact of the black orb that it had bore skyward on its summit was that of a cannonball dropped by God. Water sprayed outward in blue-black sheets and the air cracked with sound of its assault.

In a panic, Professor Essepi looked around for Dr. Slyce, but his former associate had disappeared into the mist.

A febrile wind had begun to move through the dark curtains of stench that hung in the air. It pushed its way across the waters this way and that like a starving predator hunting for meat.

The Portuguese pointed at the large black orb that rode the water and shone in the thin-blood moonlight like polished anthracite.

“What do you suppose it is?” asked the first mate.

“Satan himself,” scowled the Captain.

Cherney put in, “Hell can’t be far behind, sir.”

“Hell has already arrived,” said the Captain.

“Feels like it’s watching us,” said Mr. Abilio.

Captain Baker said nothing.

Professor Essepi, after his transient episode of self-possession and intelligent thought, slipped in his own vomit and hit the deck planking hard enough to jar his teeth. He despised being at sea more than anything single thing that he had endured in his lifetime. He had made his decision to go solely to curry favor with Secretary Marshall, solely to increase his own personal power. If the bedlamite died, that would be that. The Professor had never really believed a word Dr. Slyce had said. It had only been important to show the Secretary of the Navy— whom he still considered as mad as his bedlamite son— that he was making a serious effort. For what? Now he lay in his own vomit, needing another drink and debated the merits of throwing himself into the ocean.

“Take my hand,” the Captain called to him.

“Have you got a drink in it?” asked Professor Essepi through a twisted grimace.

The Captain was helping Professor Essepi to his feet when screams from the direction of the bow pierced the foul air. They were high and urgent and short-lived.

“Stay where you are,” shouted Captain Baker, and the men froze where they were, but looked around at the thickening fog as it pressed closer. “I said stay where you are. Stay together. Mr. Abilio, take three men and investigate.”

The Portuguese, his knife held before him in one hand and a lantern held off to high and off to his left side with the other hand, chose three sailors— one of them Cherney— and moved toward the now silent bow. The fog opened and closed around them quickly, and after a few steps into it, they disappeared from view completely, like magicians vanishing in a puff of smoke. Although the light stilled bobbed up and down for a short while like an uncertain ghost, as the moments passed, the Captain saw it diminish into a gauzy yellow glow, and when it disappeared entirely, he wondered for a moment if it had ever been there to see at all.

The three men led by Mr. Abilio moved slowly through a fog that seemed little more than a vaporous stench.

“I can hardly breathe through this, sir,” said Cherney.

“Keep your mouth shut,” said Mr. Abilio

After a time had passed, and they had moved half the length of the ship, Cherney said, “Sir?”

“I said keep your mouth shut,” said Mr. Abilio.

“I think we’re alone, sir. Mallory and the other seem to have wandered off in this mess.”

At that very moment, the tip of Mr. Abilio’s boot stubbed something, and he stopped straightaway.

“Cherney?” he said.

“Yes, sir?”

“Don’t move.”

Mr. Abilio bent his knees so that he was closer to it, and then lifted the side of the bloodied boot with the tip of his saber and moved it closer to the muted lantern’s glow so that he could get a closer look. A shard of bone stuck from the mouth of it, and a trail of cruor smeared the planking beneath the leather.

“His foot’s still in it?” croaked Cherney. “Somebody cut it straight off?”

“No,” said Mr. Abilio. “Someone or something ripped it off his leg.”

“Then where’s the rest of his body?” whispered Cherney.

From somewhere close by in the brume, they heard a loud splash, as though someone had jumped overboard. The sound was difficult to place, but Mr. Abilio straightened and turned this way and that.

“That must be Mallory,” said Cherney. “He’s fallen overboard. The poor bastard can’t walk if he’s lost part of his leg. We’ve got to go after him.”

Mr. Abilio reached for Cherney’s arm, but the man was already moving away. “Are you crazy? Stay where you are,” he snapped. “Don’t move. Do not take one step further.”

As Cherney disappeared completely into the murk, Mr. Abilio heard him say over his shoulder, “But it’s my chum Mallory, sir. I can’t let him drown. He’s the only friend I have.”

Mr. Abilio did not go after him. Instead, he stared at the spot where Cherney disappeared and shook his head. Seconds, later, he heard a liquid scream rise and fall like a lingering last note, and he began to step backwards very slowly, very quietly. Although he heard urgent questions shouted at him from behind, Mr. Abilio kept moving backward, keeping his saber in the ready position. He slipped and went down to one knee with a sound like a log hitting the planking. By a miracle, he dropped neither the lantern nor his saber. For a moment he stayed put on that one knee. The thick vapor seemed denser near the deck, and it was harder to breathe. As he knelt there, the acrid fog seemed to combine with his sweat to form an acidic film that was burning his skin. His eyes began to water.

He keened his ears and imagined he heard something heavy and wet being dragged across the deck. Mr. Abilio jumped to his feet then turned and ran back in the direction from which he had come.

Upon Mr. Abilio’s return, Captain Baker had dragged Professor Essepi into his quarters and braced him against a wall.

“If you’re too drunk to stand, then sit.” The Captain sat on the edge of his table and glared at the Professor. “You’re a sorry sight,” he added.

“I resent that,” said the Professor.

The Captain leaped up and towered over Professor Essepi as though he were about to strike him.

“I don’t care what you resent,” he screamed. “What have you gotten us into and what is that accursed ball of blackness floating out there not fifty yards from my ship? You are not only a drunk, you’re an idiot, sir. How you got a Presidential order—“

“Secretary of the Navy is more of a bedlamite than his son,” put in the Professor and, inappropriate to the moment and his breeding, he burped.

His head felt flush and the front of his coat was covered with something foul that his own stomach had manufactured. He was still confused by Dr. Slyce’s words. If the doctor could not cure the bedlamite, then why had he demanded that the Cretan priests be summoned and brought on this voyage? What was that all about? What was the doctor himself after?

Before Professor Essepi could respond, he heard an agonized scream as sharp and hard and futile as the word “no” shouted out by a man at the end of a plank. The shock of the scream drove the Professor backward two steps where he rested a hand on the other wall for support.

“What in God’s name was that?” he asked.

A second scream tore through the mist. It was low pitched and urgent and expanded out into the night like a foghorn.

“Mr. Abilio,” shouted the Captain. When there was no immediate response from his First Mate he smacked his right fist into his right palm and cried, “Can no one hear me through this accursed fog?”

A tortuous third scream rose around them in the night as though someone were being branded. The man’s wail agonized through the night with a tremulous, plaintive exhortation for surcease. Professor Essepi felt as unable to move as if his boots had been screwed to the deck. He saw that Captain Baker, too, stood transfixed. The vaporous fog had encased their movement as surely as if they were dolls held in place by cotton in a miniature display case.

Professor Essepi looked at the Captain through the thin yellow haze that had spun its way through the Captain’s cabin like a water spider’s web. The man’s skin was amber in the lamplight; it seemed to Professor Essepi that he was seeing the seaman through a death shroud.

“Stay close to me,” hissed Captain Baker.

The Captain opened the door and strode into the darkness. Professor Essepi bolted after him so that he would be left alone, separated forever from the others by the swirling darkness that suffused the doomed ship.

“Wait,” he croaked as he hurried after the Captain’s disappearing form.

Terror charged through him and he lurched forward like a madman. When the Captain stopped at the edge of a swell of urgent voices, the Professor almost crashed into his back.

“Stand aside,” cried the Captain. “Stand back, I tell you.”

Professor Essepi pressed behind the Captain as though he were his shadow. The night itself was tumescent with cabalistic terrors and he feared separation more than injury.

“What is it?” he cried when he heard the Captain.

Dark forms coalesced around them, their murmurations buzzing through the vapors like an evil hymn. The Captain reached back and seized the Professor’s shoulder as though he would fall to the deck if he were not supported.

“Professor,” he said, “Professor is that you?”

“Yes, it is I.”

Professor Essepi’s voice cracked like a splintering mast.

“What does this mean?”

The Captain’s hand raised and led the Professor’s eyes up the armor plating to where three pairs of feet hung, blood dripping down from their toes to pool on the deck below. Still the Captain’s finger levitated upward to the stained robes, up higher to where a metal spike protruded from the chest of each man, pinning them to the iron side of the ship. Sinister swirls of fomenting fog concealed their faces, but the Professor believed that their eyes would be wide open and staring straight ahead in horror.

“It’s the priests,” he said. “Someone has impaled them.”

Mr. Abilio appeared by shoving aside a seaman.

“I’ve been overhead, sir,” he said. “Dr. Slyce must have hung them over the edge and spiked them up one at a time.”

“What are you saying?” demanded the Professor.

“There is no one else with the strength to do it,” accused Mr. Abilio. “Those spikes were hammered through iron plate.”

Looking down, Professor Essepi saw the livid pool of blood extend a dark finger toward his boot as though to inculpate him. The broken lightning crosses of the priests lay shattered on the deck. When he raised his head, he saw that the three priests hung above him like meat on a hook.

Captain Baker snatched up the Professor by his coat and slammed him against the wall. A pair of bloodied feet dangled on either side of him. The Captain pressed forward so close that he could feel his breath on his face.

“Where is he?” he growled.

“I don’t know. I swear it. I had no idea. This is… this is madness.”

“I asked where he was.”

Enraged beyond words, Captain Baker repeated the arrogation and bounced the Professor’s head off the iron sheet. The impact caused the Professor’s mouth and eyes to fly open in shock and his consciousness wavered like a flickering flame.

“I tell you, man, I don’t know. This is beyond me.”

“Give me your knife, Mr. Abilio,” said the Captain in a steady voice.

“Ay, Captain,” said the First Mate.

Vague faces materialized in the mists that surrounded them and the Professor saw with deepening horror the utter disgust and fear that contorted their visages. The Captain held him high with one hand and with the other brought the point of Mr. Abilio’s knife to his chin.

“Let me do it,” cried one.

“Gut him,” screamed another.

“Nail him up like the others,” offered a faceless tormentor.

“For God’s sake, no,” yelled the Professor. “I had nothing to do with this.”

“You brought them on board. You brought that monster on our ship. You have to pay,” called someone else.

“Quiet, all of you,” commanded the Captain.

He brandished Mr. Abilio’s knife before the Professor’s face.

“By the feet of God himself,” he said, “I’ll cut your throat from ear to ear if you don’t tell me where he is.”

The blade glimmered with a dull light.

“Captain,” cried a man behind them.

“Silence, I said,” roared the Captain.

“The water, sir— it’s alive.”

The Captain’s fingers flew open, the Professor dropped to the deck, and Captain Baker spun to face his crew.

The orb lit up and dazzled the night with colors no man had ever seen, and in its dark radiance the sea had indeed come alive with hideous undulating forms that moved inexorably through the diseased waters toward the ship like an unholy army of madness. The crew shrank back toward the three dead priests with a cry of utter terror.

“God’s grace,” cried one of the men. “Jesus and Mary be with us.”

“Man the cannons,” shouted the Captain. “Drive them back.”

“Not the cannons,” screamed Professor Essepi. He had stepped to the Captain’s side, his face wild and feral.

“I’m on your side, believe me. But I told you, as God is my witness we cannot risk igniting the gas.”

The Captain stared at the Professor. His right hand still clutched the knife so hard that his fingers throbbed. For a moment, he looked as though he would plunge it straight away into the Professor’s stomach. Then he faced the crew.

“The Professor’s right,” he shouted. “No cannons to save us tonight and no pistols. Swords and knives only men. Hack anything that tries to board this ship to pieces.”

No one moved.

“If you do not move, I’ll cut you down myself.”

After an uneasy silence, the men moved toward the railings, drawing blades as they did so, their faces lit with fear of something worse than death. The dark waters around their ship churned with monstrous shapes that seemed part man, part fish, and something vaguely reptilian.

“Behold the armies of Dagon,” boomed a voice from above them.

“My knife, Captain,” urged Mr. Abilio.

The Captain backed away and looked up at the towering dark form of Dr. Slyce who stood straight and imposing as a totem. One arm stretched high above his head and he held a staff as though he were calling down the Powers of Darkness. Atop his head was fixed golden metalwork that flashed back the unholy colors of the orb.

Captain Baker stared at Mr. Abilio for only a moment, then pressed the knife into his First Mate’s hand.

“God be with you,” he whispered.

Mr. Abilio flashed his teeth, and then disappeared into the vapors.

“The Eye of Dagon has seen the sacrifice and approved,” yelled Dr. Slyce. “Through the mouth of the bedlamite, the Deep One will speak.”

The men gasped as Dr. Slyce lowered his staff and jerked forward the madman to display him to the crowd. His eye sockets were black deeper than night, and his wild hair splayed from his head like Gorgon snakes. His clothes were ripped and hung on him like torn sails on a mast. He opened his mouth wide and his cavernous voice bellowed through the night.

“Um dklifhatg’n,” he yelled. “Cthulhu. Ph’nmglui mglawy panafh Cthulhu R’ley wgah-narnpf. Fhataga.”

“Proclaim the oath of Dagon with me or die,” called Dr. Slyce.

In the waters behind them, the Eye of Dagon flared again with spectral, unspeakable brilliance.

“Id ia,” howled the bedlamite.

Dr. Slyce pointed with his staff over the men’s head toward the Eye. “They Eye of Dagon has witnessed the sacrifice,” he repeated. His staff dipped downward and pointed at the impaled priests.

From the sea came a barking, croaking chorus, and the men looked back and forth between the monstrosities that churned through the waters toward them and up at Dr. Slyce’s towering figure. The diadem fixed to the doctor’s head began to pulse and glow a panoply of clashing colors that caused the men below to be overcome with vertiginous waves of nausea.

“Join us or die. Eternal life for those who take our oath. Freedom from death. The power of the Elder Gods will reign again and we will sweep mankind before us. We will rule the oceans from pole to pole. Mene, mene, tekel, usharsin sech.”

The bedlamite opened his mouth again, and this time from it came a roaring like all the waters of the world converging in an obscene cacophony of disconsonant contention. Men covered their ears and dropped to their knees as blood poured out from between their fingers and they wailed in pain.

Captain Baker alone stood.

He, too, had covered his ears and his face had twisted in a melted wax replica of agony but he was transfixed where he stood and he did not pull his eyes away from the madman who unleashed his aberrations into the night.

The bedlamite cried out as Mr. Abilio appeared at his back and, with one quick slice, slit wide the man’s throat and blood rushed out like water from a pierced bladder. With a thrust of his foot he sent the bleeding madman over the edge to slam face first into the deck at Captain Baker’s feet.

In a violent fury, Dr. Slyce swung his staff at the First Mate’s head the exact moment Mr. Abilio plunged his knife into the doctor’s stomach and ripped upward. The staff cracked into the Portuguese’s head and, as the Doctor let go of it and pulled his hands to his stomach, the First Mate hit the lower deck beside the Captain. His neck snapped on impact, and the man lay still. Blood and bile drained from his mouth and he coughed once, gurgled, and died. The Captain bent to one knee and stared in disbelief at Mr. Abilio’s corpse, then stood and looked to the upper deck where Dr Slyce’s form lay struggling. As he watched, the doctor dropped, then pitched forward and slid over the edge toward him. The Captain took a step back, and then stopped as he saw Dr. Slyce’s body hook on the protruding spike of the middle priest and hang from him with a final shudder.

“Captain,” cried one of the men.

The urgency in the man’s voice caused the Captain to tear his eyes away from the sight of Mr. Abilio’s body. As he turned, his face hardened into a mask of rage, and then fell slack as he beheld slithering, antropoid fish creatures pulling themselves over the railing. The Professor stood beside him staring down at the prone, discarded figure of the bedlamite. Coincident in time the Professor unaccountably dropped to his knees and cried out for the loss of the madman as the Captain drew his sword and charged to the aid of his men who were hacking at stabbing at the hideous fish-men. The sea creatures tore and ripped at the sailors. Screams and battle cries mingled with yelps and keens as men and monsters alike slipped and fell in a mixture of blood and ooze.

As the Professor cradled the body of the dead lunatic in his arms and spoke calm, soothing words to his corpse, the sailors and the admixture of reptilian fish-man creatures savaged each other on the decks as knives were plunged deep into grey-green slick torsos to release dank melodious streams of fluid while teeth and horned elbows ripped flesh and sinew away from their human prey. While the Professor cupped a hand under the bedlamite’s skull to keep it from flopping up and down as they rocked, hordes of creatures continued to clamber over the railings on to the squirming mass of bodies. When the Professor broke down in tears, at that exact moment an almost formless head rose from the stinking mess of death and thrust a spiny pike through Captain Baker’s lower jaw with such force that it shot straight through his head and into his brain. The Captain shuddered and fell back dead on a squirming mass of entrails that had spilled out of an aberrant tentacled thing that lay writhing behind him. Tears streamed down the Professor’s face.

As the squealing, chaotic mass behind him swelled into a sonancy of psychopathy and aberration, the Professor finally set down the dead bedlamite and rose again to his feet. His face was as stramineous with grief as if he were jaundiced. His eyes were wide open and streaked with broken blood vessels. He came around like an automaton and gazed at the carnage before him. His lower jaw dropped and hung slack. The gory scene receded to the seared edge of his vision, eclipsed by the image of the Eye of Dagon rising above dark waters, lifted by a an undulation of alien colors.

Fish-men dragged the corpses of mutilated human and monstrosities alike over the ship’s railing and disappeared into bloodstained waters as the Professor recoiled in horror when he realized that the Eye of Dagon was actually looking him. The realization that the root cause of insanity was alive shattered his mind into fractured fragments of consciousness. His vision filled with the utter alien nature of the Eye as he stepped into the open blood cavity of Captain Baker’s mutilated abdomen and continued toward the railing. The fish-men moved past him as though he were not there, and there was no human being left alive to notice him.

The railing stopped him, though for a moment he teetered at its edge as though he would fall over, but he did not. He was unaware that the fish-men were now gone back into the waters or that they had taken every last man and body part over the edge with them. The Eye of Dagon held his gaze.

“Wgah-nagl Cthulhu,” he cried out.

The Eye flashed brighter and suddenly the Professor thrust both thumbs into his eyes and shrieked in torment as he repeated the action again and again screaming “Y’ha-nthlei” with each thrust until his face was obscured completely by blood.

As the madman dropped to his knees and began to tremble violently, the Eye of Dagon dimmed and descended into the stained waters from which it had come. Overhead, a fine, polluted rain began to fall and it grew in force and intensity until it dissipated the dark vapors that had risen from the sea and washed clean the deck of the U.S.S. Vincent where Professor Essepi now pounded his forehead against the deck.

Three days later, on an afternoon clear and clean with wisps of elusive white clouds brushstroked across a beryl backdrop, the crew of the Mohican class U.S.S. Kearsage, captained by Captain Charles W. Pickering, located the U.S.S. Vincent and its lone survivor. While attempting to guide the blood-crusted lunatic with bloody holes for eyes back to their skiff, the madman sunk his teeth into a sailor’s hand and bit off the man’s index finger. While the man screamed, the bedlamite flapped his arms in crazy windmills and ran straight for the ship’s railing.

His body was never found, but Seaman First Class Bissoon swore til his dying day that when Professor Essepi’s body hit the water, scaled tentacles reached up and pulled him under.