by Michael A. Clark

“That was good work, James,” said Thaddeus. “I knew for whom to summon if there was hope for surviving his grievous wound.”

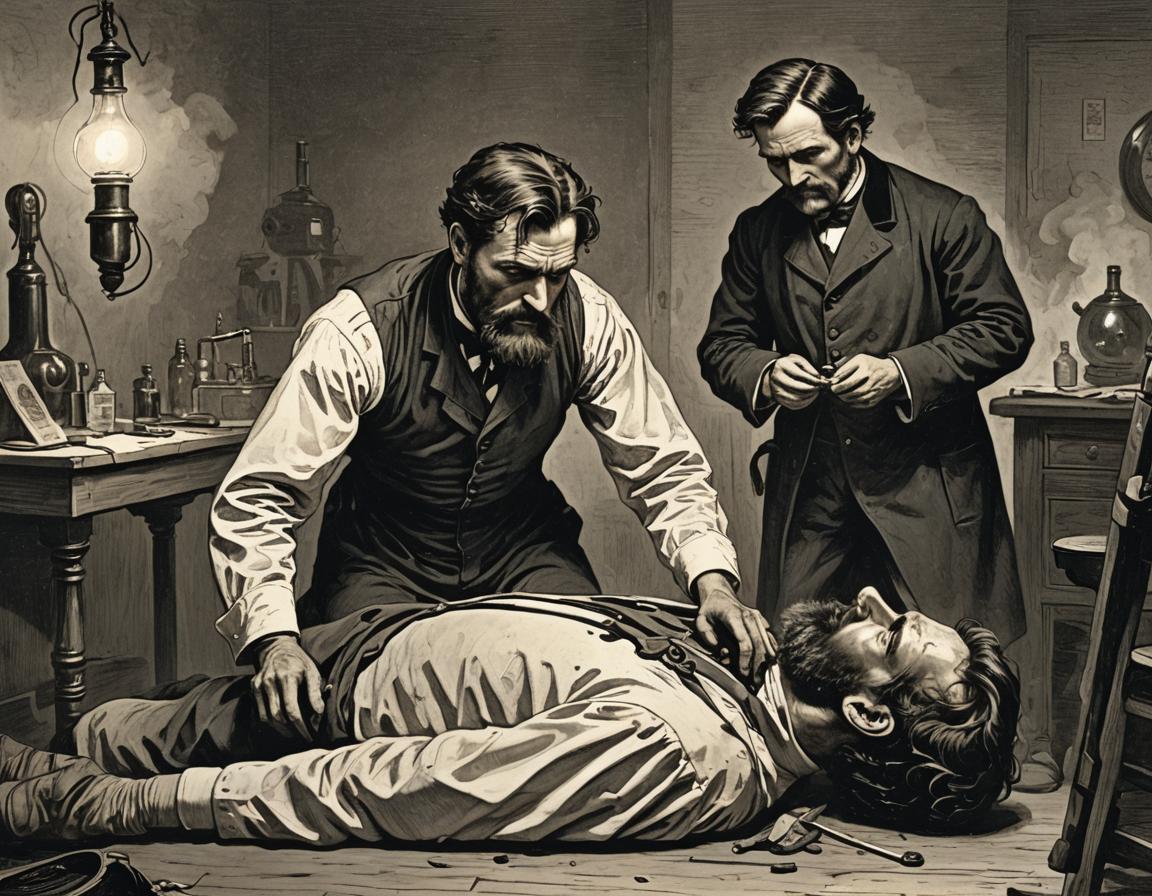

The gaslight lamps hung from the patterned wallpaper burned with tired light, casting weary shadows over the outer room. The stench of dried blood and sweat filled the air. In the next room lay the patient, breathing shallowly.

“I did my best,” I replied. Tension shackled my shoulders and my arms felt as though weighted with lead. “I did not care for the audience that insisted on viewing my efforts.”

“They were there to hear his last words. What he might say before slipping off this mortal coil. Do you blame them?”

“I just thought it ghoulish to have close to a dozen of Washington’s finest citizens crowded about me as I operated.” I rolled my shoulders while turning my chin left and right as far as I could.

“Perhaps they are ghouls. But able to say that you heard the final utterances of…”

“His final utterances will be delayed, good Lord willing, if my efforts have anything to say about it.” I finished the stretching routine I’d performed a myriad of times before. After Antietam, Gettysburg… Too many times.

“Indeed,” said Thaddeus. “What is your medical opinion of his condition, Doctor?”

I managed a wan smile. Thaddeus and I had been fast friends at Harvard, where he pursued law as a career while I medicine. He had done well for himself and was now a trusted advisor to government. I had a small practice in Ithaca, and Emily and I were happy there.

Until the war called me away.

“He will lose sight, at the least. The ball took a large slice of his brain matter with it before disgorging the right eye. A pistol round impacting at such close range, with such force… it is a marvel he’s not already dead.”

Would he know of our conversation, lying next door in his battered condition?

“We know so little of the body and the mind, and how they rely upon each other,” I continued. “If there were a way to somehow see inside his shattered skull, to be able to mend the tears and release the pressures…”

“He could have no finer doctor attending him, James,” said Thaddeus. “Surgeon General Leale and Doctor Barnes acquiesced to your level of skill.”

I was warmed by Thaddeus’ kind words, and I knew deep inside that I’d performed as well as my skills and experience would allow. “In a hundred years, what could we do for such infirmary? For now, I poke and prod and cut and sew, like Frankenstein groping for the secret of life. Only I wish but to save a life, not create it.”

“I am proud to call a man such as you friend,” he said. “Now, what shall we tell the pressmen gathered outside, about the condition of your patient?”

“Oh no,” I said, snapping erect. “I will not face that flock of ink-stained vultures! I am a doctor, not a political hack spewing…”

Thaddeus smiled.

“I’m sorry, old friend. I did not mean to insult.”

“None has been taken.”

God, I was tired. The murderous villainy had occurred the night before. Or was it two nights ago…

A knock on my hotel room door, as I was penning a letter home to Emily after a long day of lectures about operations under battlefield conditions. A watchman declaring that Thaddeus had sent for me, with a request for my services under dire and secretive circumstances. The bare details of the assassination attempt adding to the confusion and rage swirling in the damp, cold streets of the newly reunited nation’s capital.

Ceaseless hours hunched over the tall pale figure, battling death itself. He was just another soul to save, I thought as I’d worked. Like so many I’d saved before. Like so many I hadn’t.

“Have they caught the scoundrel yet?” I asked.

“No,” sighed Thaddeus. “But the hunt is on. The bastard’s co-conspirators have been apprehended, at least some of them. The word is out. Justice will be done.”

“Co-conspirators?” I said, realizing that this blow was struck not at one man, but at the nation itself. “Who was he that pulled the trigger?”

“Some actor,” said Thaddeus. “A Southern sympathizer who never mustered the courage to fight for the ‘cause’ he professed to support, but who cravenly sought to slay the leader who vanquished the vile secessionist serpent.” He reached for a thick bottle upon the table behind him. “A whiskey, to revive the spirits of the man who may have saved the Union?” He unstopped the cork and poured a dusty glass three quarters full.

I recalled that Thaddeus himself had not served at the front.

“I have promised Emily that my last drink would be my last.” My wife had become enamored with the newly popular Temperance Movement that was sweeping upstate New York. I didn’t quite agree, but… “A vow is a vow,” I said.

“After a day and a night’s work such as you’ve done, I would grant you a dispensation.”

Was it nighttime already? Why else would all the room’s lamps be lit, and the shadows so dark? God, I felt so old. I took the glass, and drained half of it. Immediately I sputtered, hacking most of the liquor back up my throat where it burned anew before resettling in my roiling stomach.

“My, it has been some time since your last drink!” said Thaddeus, with a sparkle in his eye. “You took the devil’s brew much smoother back on those spring nights by the Quad, James.”

“I was a foolish young man then,” I croaked. The liquor almost immediately resumed the work of relaxing the muscles that my exercises had begun. I glanced at the remains of the liquid fire in the glass, dim caramel swaying in the soft gas light.

“What the hell,” I said, and emptied it.

“I don’t predict a wet-brain dwelling under a bridge for your future quite yet,” said Thaddeus as he joined me.

“What of the future, old friend?” I asked, as the spirits warmed me.

“Much of that depends on the good work you’ve done, and how your patient will recover.” Gentle rain began tapping on the eves of the roof, and I could hear a whip crack against the side of a carriage as its driver urged horses to shelter.

“He won’t be the same man,” I said bluntly. “Aside from the physical damage, he may not be able to speak, or even to write. He who led us through so much sorrow and violence will be a shadow of himself.”

Thaddeus’ face turned grim.

“That would be a tragedy,” he said, pondering his glass. “Despite what you might think of my chosen career path, James, I do not relish the process of politics. I am more drawn to the personalities, the visions of men of power, the will to do what needs to be done. Processes… processes can become like an illness, draining the body of vital energy.” Thaddeus absorbed the rest of his drink. “Congress, now that the Union is one again, will be riddled by process. And there are many who will want that process to punish, not to heal.”

“This isn’t going to be an easy peace. That is what you are saying?”

“It will be a peace. The peace of a brother conquering a brother. I’ve heard things in the halls of power in this city. Revenge, humiliation, destitution… all enforced in the name of the Union. The South must never rise again…”

Thaddeus looked forlornly towards the whiskey remaining in its bottle. “I would gladly empty that bottle tonight. But the problems would remain.”

He squared his shoulders and stared at me. “He must not die, James.”

“I know. But as I said, if he lives, he won’t be the leader we’ve known.”

“So if he’s a figurehead, as mute as the foremast on a steam frigate? As long as he lives, the man rallies the forces of right! If bound to a chair and drooling in a spittoon all his waking hours, he can still help mend this nation whole.”

“And how will he accomplish this herculean task, if chair bound and mute?” I asked. “Will… others, speak his words for him?” I polished the rim of the glass I’d emptied with my finger, the old familiar ember in my stomach.

“I know good men who will honor his words, and his deeds. We can hope to present our interpretation of the man’s courage and strength truthfully.”

“We?”

“James, I have friends who are planning a great revival of his Gettysburg speech, to be delivered in town squares around the nation. Orators promoting the ideal of nationhood rebirthed after a terrible strife. It will take time. But the bonds of nationhood will be reforged between North and South. They will!”

“And what of the silent mannequin left behind by your glorious paid speeches?” I asked. “What of his wishes, his dreams, his family? Has he not sacrificed enough for this country? Would you enslave him for the rest of his crippled life to your holy cause, however valiant it may be?”

“Enslave?!”

“What if the man is tired, wanting only the peace of the grave and of Heaven?” I asked. I’m not a pious man. Church services were Emily’s passion, not mine. But I ‘d hope there was a Lord above that could make sense of the uncountable horrors I’d seen in the past few years.

“Do you think me a fool?” Thaddeus asked.

“No, old friend. Nor a nave,” I said. “I… just question the supposed good in the course of action you’ve described.” The faint hiss of gas through the lamps sounded in the silence between us.

“What more do you need to see to your patient’s recovery, Doctor?” asked Thaddeus, and I could tell by his tone that he was not prepared to further discuss his grand program.

“I will write out a short list of supplies and medications needed to minister to the patient,” I said, reaching for the pen and sheave of paper that was on the table. “I’ll also dictate my view on how treatment should be provided for the next several days… If we are so lucky.”

“I will see to it your recommendations are followed to the letter,” said Thaddeus, firmly. We stared at each other for a long moment.

“I need to go home, old friend,” I said. “It’s been too long, and now this…”

“Of course.” Thaddeus gathered his hat in his hand. “Blessings to you and your family, James. And please don’t judge an old friend’s speech too harshly, until you may view it in the calm light of time’s passing.”

He was gone, with the soft closing of a door. And I was alone, with my pen and paper and the future of a struggling nation. The lights burned a shade dimmer, and rain whipped again against the thick windowpanes and the tortured breathing in the next room.

The End